High rainfall, lower salinity in the Chesapeake Bay

by NOAA Fisheries 15 Nov 2018 17:01 UTC

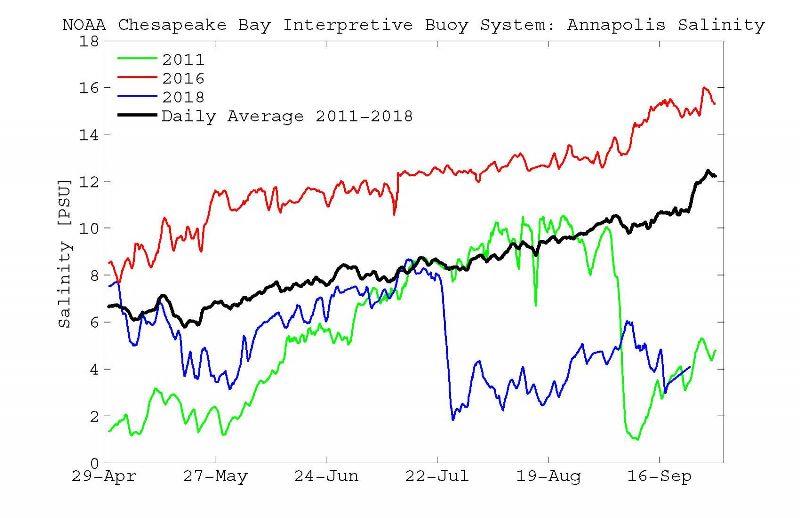

Salinity at NOAA CBIBS Annapolis May through September © NOAA Fisheries

Here in much of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, 2018 has been a bit on the damp side—to put it lightly. The area has experienced higher-than-average rainfall, leading to record amounts of water flowing off the land into the Bay.

We know what all that rain means for people—traffic-filled commutes that take longer, grumpy kids who want to play outside, rescheduled baseball games, and uncooperative vegetable gardens. But what does it mean for the Bay—and the critters who live in it?

One of the main ways that significant amounts of direct rainfall and increased freshwater flow from the Bay's tributaries can affect the Chesapeake is by lowering the salinity level of the Bay. Salinity, measured in practical salinity units (PSUs), ranges from 0 for fresh water to about 35 in the ocean. The Chesapeake Bay's geography takes it from the mouths of freshwater rivers to where the Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean, so it includes a wide range of salinities.

Salinity at a given location can vary greatly, too. Over the course of the year, salinity often follows a pattern based on rainfall in the area, so that the waters are less salty—lower PSUs—from fall through spring when the Chesapeake watershed generally experiences higher precipitation. Over the summer, salinity slowly creeps up as rainfall drops.

But some years are quite different. The following graphs show salinity at the Annapolis and Stingray Point CBIBS buoys from May through September, highlighting the average from 2011 through 2018 and a few notable years. On these graphs, the heavy black line shows the average salinity off Annapolis from 2011-18. It's interesting to track a dry year—2016—and see how salinity was higher than average, and to see what heavy rainfall in 2011 (a wet spring followed by a drier summer followed by tropical systems Irene and Lee in the fall) and 2018 (wet May, drier June, very wet July followed by Florence in September) do to salinity levels.

Approximately 40% of the freshwater flow into the Chesapeake Bay comes via the Susquehanna River. When the Susquehanna watershed, primarily in Pennsylvania and New York, gets a lot of rain, the Chesapeake Bay gets a lot of rainwater and runoff. The Conowingo Dam, about 10 miles upstream from where the Susquehanna meets the Chesapeake, provides electricity generated by hydroelectric power.

Sometimes, when the water level behind the dam gets too high, gates on the dam must be opened to increase flow in order to relieve pressure on the dam. When that happens, freshwater flow to the upper Chesapeake can increase significantly, lowering salinity. In the following graph, gate openings are indicated by increased flow from the Conowingo—leading to lower salinity at Annapolis and Stingray Point CBIBS buoys.

These changing salinity levels can affect living resources in the Bay. While how fish, crabs, and other critters may be affected by current conditions remains to be seen, scientists know from past research and observations that some living resources are affected by low salinity events.

- Sea nettles prefer the right blend of water temperature and salinity--and with fresher water, nettle numbers are likely to be down. While this may be great news for boaters and swimmers who don't want to experience the stings they bring, sea nettles are an important part of the Bay ecosystem. They eat zooplankton, fish larvae, and also comb jellies--which in turn eat oyster larvae. So fewer sea nettles may mean fewer oyster larvae.

- Oysters are particularly susceptible to changes in water conditions like lower salinity because they grow as part of reefs--and therefore can't move to find conditions they prefer. While lower-salinity waters can reduce the prevalence of diseases that affect oysters, they can also negatively affect oysters' ability to reproduce.

- More mobile critters--like fish and crabs--may seek different areas of the Bay for their habitat as salinity levels change. For example, within the Chesapeake Bay, male blue crabs generally prefer fresher waters in Maryland and the upper tributaries, while females like the saltier waters in the mainstem of the Bay and Virginia. Blue crabs use different areas of the Bay--with different salinities--during their life cycle, including high-salinity areas as larvae. So different salinity levels may affect where blue crabs are found.

- Similarly, rockfish use waters with differing salinities during their lives as well, migrating to freshwater areas to spawn, but then generally spend the rest of their lives in brackish or salt water. They grow more quickly when in water around 7 PSU then they do in water of 0.5 or 15 PSU. Depending on the timing of events, fresher water may enable more zooplankton to exist—and zooplankton is an important food for young striped bass.

- Menhaden, which are food for many Bay species and an important commercial fishery as well, are quite salinity tolerant, and can live in fairly low-salinity waters. But how this low-salinity event may have affected how and when menhaden larvae move into the Bay is not well understood.

With so many questions remaining, scientists are eager to dig in to data. The Chesapeake Bay Program's

Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team plans to focus on the topic at its December meeting, giving Team members some time to analyze data before they meet in person to discuss potential effects of this rainy year on the Bay's living resources.