Lava flow time portals: Understanding the development of deep-water coral communities

by NOAA Fisheries 20 Dec 2019 06:42 UTC

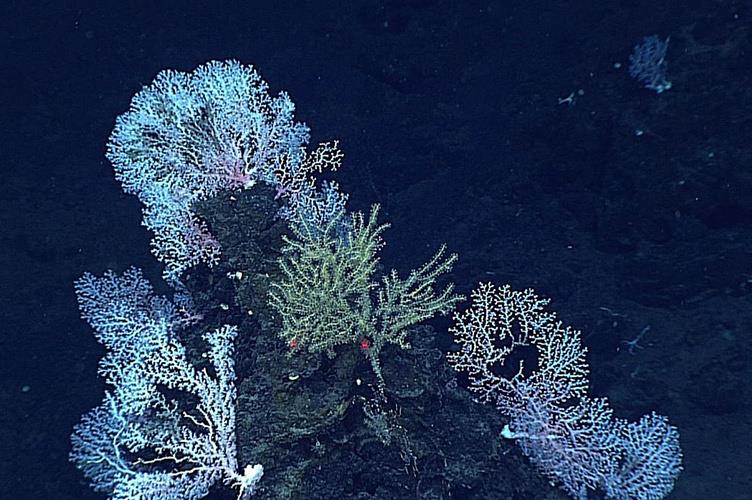

A dense community of deep-water coral on a 143-year-old lava flow located at South Point, Hawai‘i in 2015 © NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Deep-water coral communities are some of the most diverse and productive environments in the deep ocean. They provide habitat for an array of organisms including some not yet known to science. Some corals are known to live far more than 2,000 years, but grow very slowly—less than a millimeter each year. This makes them very difficult to study within a human lifetime.

To understand how deep-water coral communities develop over time, researchers surveyed the community of deep-water corals growing on the lava flows of the island of Hawai'i. Since we know when the flows occurred, they essentially act as "portals in time." They allow us to view coral communities over a range of ages in the same environment. Hawai'i is probably the only place in the world where such a study could be performed due to its continuous and well-known volcanology.

On the leeward coast of Hawai'i, researchers deployed the submersible Pisces V and the remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer. They surveyed six lava flows and an older coral community growing on fossil carbonate nearby. Within a 60-mile area, each site was a different age: from 61 to 15,000 years old!

Comparing deep-water coral communities growing on these substrates of vastly different ages revealed a pattern of ecological succession extending over centuries to millennia. The communities changed in structure and diversity over time. The relatively fast-growing red coral (Coralliidae), which reaches maturity within 60-100 years, colonized new lava flows first, dominating the community. With enough time, the community shifted toward a more diverse array of tall, slower-growing corals including bamboo coral (Isididae) and black coral (Antipatharia). The last to colonize was gold coral (Kulamanamana haumeaae). Parasitic in nature, gold coral overgrows mature bamboo corals. It is also the slowest-growing coral within the community, growing thicker each year by just 0.04 mm—less than the width of a human hair.

This is the first study to examine the growth rate of deep-sea coral communities over a period of more than 100 years. Our research suggests that a Coralliidae community in Hawai'i can develop within about 150 years. The larger, slower-growing communities of gold coral could take thousands of years. These findings have important implications for the conservation and management of deep-sea ecosystems.

Watch a video from this research by videographers aboard the NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer. In it, authors Meagan Putts, Frank Parrish, and Sam Kahng speak about how the field work for this research was accomplished.