One of the great modern-day sea adventures

by Shane Granger 22 Feb 2024 22:29 UTC

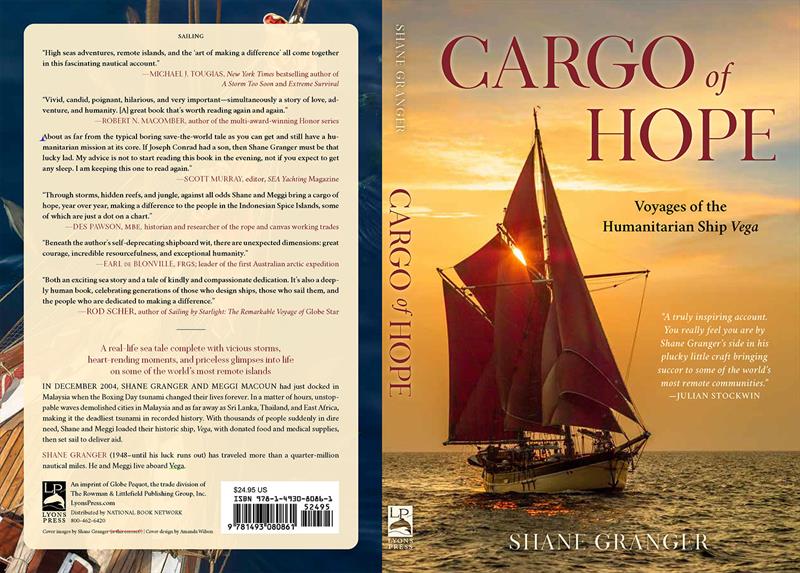

Cargo of Hope novel jacket © Shane Granger

Writing in a style that is both informative and engaging, yet with a playful sense of humour, Shane Granger takes the reader, whether he be an armchair sailor or deep-sea mariner, on a magical journey from the boat’s beginning in the 1890s to modern-day dramas of sailing through dramatic storms or the beauty of exotic tropical islands. Meeting the people on those remote islands will open your eyes to an entirely different world. The action is intense. The magic of sail captivating. But most of all “Cargo of Hope” is about people.

Beneath the author's self-deprecating shipboard wit, are unexpected dimensions: great courage, to keep risking his boat and crew; incredible resourcefulness, stretching his limited fuel and food resources to the limit; and exceptional humanity. A true modern day adventure, with ties to history, that leaves you wanting more. Well written, remarkably compelling and deeply entertaining, Shane lives a life that many of us dream of. Yet while most of us have a somewhat selfish image of this lifestyle, he turned the dream into a selfless experience on a shoestring budget.

About the Author

Shane Granger (1948- until his luck runs out) fell in love with the sea since the age of seven. Having worked as a radio announcer, advertising photographer, boat builder, director of museum ship restoration, and bush pilot, he always returned to the sea. Shane has thousands of miles under his keel, including a square-rigged brigantine he salvaged from a beach in West Africa – a vessel he once single-handedly sailed across the Atlantic without an engine or functioning rudder.

After crossing the Sahara Desert with a Tuareg caravan, being kidnapped by bandits in Afghanistan and chased through the Andes mountains by an assortment of lunatics, his greatest ambition is to enjoy the healthy benefits of monotony and boredom. Shane currently lives in Southeast Asia on an ancient wooden sailing vessel with his partner Meggi Macoun and their two cats. Every year they sail over five-thousand miles delivering donated educational and medical supplies to remote island communities.

"The truth is, I never once went searching for an adventure, " says Shane. "Although, the way the damn things keep sneaking up is enough to make me want to hide in a cave. Every time I find a nice comfortable billet along comes the feckless middle finger of fate ensnaring me in yet another thrilling escapade I could do without.”

"When asked to comment on Granger’s stellar talents, Professor Hienfrick von Botamburb, honourable president of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Commas, exclaimed, “Granger! Who let that idiot lose with a word processor?”

Granger say of himself, “I believe we all dream of escaping the hectic rat race of today’s highly accelerated world. A retreat into the leisurely ways of those glorious long-ago days now sacrificed to the twin gods of efficiency and profit. Of escaping back to a time when travel was an art form in itself; a time of discovery, adventure, exotic island destinations, and of course romance. Vivid images of freely roaming the world enjoying a carefree lifestyle. For some, that means the wind powered freedom of their own sailing vessel.”

“Yet most harbor a selfish vision of becoming the perpetual tourist, visiting far away places, taking, but never partaking in or contributing to local life. Their dream is to arrive, rubberneck the islanders, consume limited local resources, dump their rubbish and leave.

“Some of the islands we assist are so remote that when we leave they do not see another out side face until Vega returns. Often they are so remote money no longer matters. There being no shops to spend it in.”

“I Originally wrote Cargo of Hope to amuse a few of our friends and supporters, who after hearing bits and bobs from our adventures over the years, began insisting I either write a book - so they can read our misadventures all at once - or shut up and order another round- with peanuts.”

“By furnishing a health worker or traditional midwife with the supplies needed to care for their community, we provide the entire community a brighter future, and ourselves with a deeply moving sense of accomplishment.”

“When we provide a child with the tools to learn, their little faces glow with happiness and I wonder, will one of these children grow up to change the world?”

“if you want a taste of what it’s like at sea on a 130-year-old sailing vessel, loaded to the gills with supplies for some of the world’s most isolated islands, enduring every kind of weather; if you want to meet and get to know people who live on those remote islands and the unimaginable problems they face just surviving—then this is the read you’re looking for.”

“For a guy who successfully failed every one of his English classes, creating this book was not easy. Between the first rough draft and final product stood a learning curve steep enough to frustrate Sisyphus.”

What others have had to say....

"High seas adventures, remote islands, and the "art of making a difference" all come together in this fascinating nautical account. Shane and Meggi have seen natural wonders few people on earth have. The reader will feel they are at sea on both fair days and in brutal storms, guided by two highly experienced sailors who have a thirst for adventure and a determination to assist others in need." -- Michael J. Tougias, NY Times bestselling author of A Storm Too Soon and Extreme Survival

I"'ve never been on a greater adventure than on the pages of Cargo of Hope. It's so full of Shane Granger's amazing experiences aboard Vega, an ages-old Norwegian-built sailboat that has taken him and his partner Meggi across thousands of miles of Earth's busiest sea lanes and yet visiting their most remote islands. Along the way, he has braved a category 5 cyclone, survived a devastating tsunami and its aftermath, sought out safe harbor among shallow shoals and dangerous seas, and traveled the rugged inland paths of remote spice islands delivering medical and educational supplies often by foot to people desperate for help."

"These pages are brimming with great storytelling about the simple but hardy people of the islands, inexperienced but dedicated crew who accompany Shane and Megi on the voyage, and interesting strangers and friends from around the world who help them carry out their very simple mission of caring for the forgotten isolated people who raise the spices you often take for granted. And Shane's very charismatic voice in telling this true life story makes for fun reading, like receiving a dispatch from sea after a long, trying voyage. His keen sense of humor and Bonhomme entertains as well as informs of a life and lifestyle that will amaze and you will come to admire. One of my favorite reads ever." --- Alan Eggleston, Booksville

"I have known of the work of Shane Granger and Meggi Macoun for several years now and have developed a huge admiration for their achievements and dedication. As a life's work, each year they deliver over 25 tons of educational and medical supplies to some of the world's most remote communities, showing how a modest input can make a major difference. It was my special pleasure to read an early draft of Cargo of Hope., A truly inspiring account of a mom-and-pop charity in a 120-year-old wooden vessel. You really feel you are by Shane Grangers side in his plucky little craft bringing succor to some of the worlds most remote communities." -- Julian Stockwin

Excerpt from Cargo of Hope

The Mother of All Storms

Ripping through an ominous sky blacker than the inside of the devil’s back pocket, a searing billion volts of lightning illuminated ragged clouds scudding along not much higher than the ship’s mast. An explosive crash of thunder, so close it was painful, set my ears to ringing. Through half-closed eyes burning from the constant onslaught of wind-driven salt water, I struggled to maintain our heading on an ancient dimly lit compass.

This was not your common garden-variety storm. The kind that blows a little, rains a lot, then slinks off to do whatever storms do in their off hours. This was a sailor’s worst nightmare: a full-blown, rip roaring, Indian Ocean cyclone fully intent on claiming our small wooden vessel and its occupants as sacrifices.

All that stood between us and the depths of eternity were the skill of Vega’s long-departed Norwegian builders and the flagging abilities of one man, who after seventeen straight hours fighting that hell-spawned storm was cold, wet, and exhausted.

Using both hands, I turned the wheel to meet the next onslaught from a world ruled by chaos and madness. Should I miscalculate, or lose concentration for a single moment, within seconds the boat might whip broadside to those enormous thundering waves, allowing the next one to overwhelm her in a catastrophic avalanche of foam: rolling her repeatedly like a rubber duck trapped in someone’s washing machine: shattering her stout timbers and violently dooming us to a watery grave.

The rigging howled like a band of banshees tormenting the souls of sailors long ago lost to the sheer brutality of such storms. Raging wind, fully intent on ripping the air from my lungs, made it almost impossible to breathe. No matter which way I turned my head there was flying water.

Only twenty meters away, the bow of our one-hundred-and-twenty-year-old wooden vessel was invisible in a swirling mass of wind, rain, and wildly foaming sea. With monotonous regularity, precipitous walls of tortured water loomed out of the darkness, rushing toward Vega’s unprotected stern. Yet, as each seemingly vertical wall of water raced toward her, its top curling over in a seething welter of foam, our brave little vessel rose, allowing another monster to pass harmlessly under her keel.

With each wave, the long anchor warps trailing in a loop from our stern groaned against the mooring bits. Those thick ropes reduced Vega’s mad rush into the next valley of tormented water, their paltry resistance the only thing preventing fifty-two tons of boat from surfing madly out of control down the near-vertical face of those waves.

As Vega valiantly lifted to meet each successive wave, she dug in her bow: a motion that left unchecked might rapidly swing her broadside. The end inevitable, as the next breaking waves rolled Vega through three-hundred-and-sixty devastating degrees until nothing remained afloat.

With helm and wind creating a precarious balance against the brutal forces of an Indian Ocean cyclone, our future depended upon a single scrap of storm sail stretched taut as a steel plate, its heavy sheet rigid as an iron bar.

While hell broke loose around us, down below the off watch lay squirreled away in their bunks, warm and more or less dry. Little did they realize at least once every eight to ten seconds I fought another giant wave intent on our destruction. Squinting and blinking, I tried to read the wind speed gauge but only glimpsed a meaningless blur of figures.

More fool me for not paying more attention to the old sailor who once advised me never to look down when climbing ratlines, or aft during a storm. It might have prevented me from almost suffering an apoplexy when somewhere around midnight I glanced astern and saw a wave much larger than the rest come roaring out of the darkness, growing in height and apparent malice with each passing second.

As if that were not enough, a rogue wave surged out of the night at a ninety-degree angle to our route. Shivers raced up and down my spine, vainly looking for a safe place to hide. Nothing in my years at sea prepared me for the giant storm-ravaged whitecap bearing down on Vega’s starboard beam.

Frozen in horror, I watched that watery monster collide with the first giant wave, roaring along its length like a head-on collision between two out-of-control avalanches determined to destroy everything in their path. A towering eruption of white water rocketed skyward in an unbridled display of violence beyond imagination.

Converging on our frail wooden boat from different directions, those twin monsters were a manifest curse from the darkest depths of my worst nightmare. Clearly, they would arrive at the same time. The one slamming into Vega like a huge bloody-minded mallet, while the other played watery anvil. And, not a damned thing in this world I could do about it.

For a split second stretching in to eternity, gut-wrenching fear seized me in its claws. No matter what I did, one of those furious monsters would roll Vega on to her beam-ends, followed by certain destruction.

Trembling from cold and fatigue, just enough time remained for me to take a deep breath before water erupted from every direction, transforming my world into a swirling white maelstrom of destruction. Frantically struggling against inconceivable forces fully intent on sweeping me overboard, I gripped the stout wooden wheel, turning it against the sideways slide I felt building. Then something struck me a fierce blow to the head. As I began losing consciousness, my only thought was, So, this is how it ends. Then my world turned black.

Battered, Not Beaten

I have woken up in a strange assortment of places during my life—everywhere from the boudoir of a French countess to a small-town jail in Louisiana—although none of them compare to being hammered back into cognizance by a few tons of ice cold seawater while lying in the scuppers of a half-foundered sailing ship. Given a choice, I’ll happily take breakfast with the countess any day. Right little stunner she was.

Battling up from the depths of oblivion is a bit like rebooting a computer. Everything starts over again from the here and now, not there and then. I had no idea where, or even who was asking the questions as awareness clawed up through unconsciousness into the raging violence of a full-blown cyclone. The boat rolled hard to port. Before I could grasp a pin rail for support, another watery fist cascaded over the rail, brutally slamming me back onto the deck. Helpless to resist such overwhelming power, the torrent spun me around, then washed me back into the lee scuppers.

In a sudden rush of awareness, reality came hurling back. I was at sea in a vicious storm battling for life, and the lives of my shipmates. I pulled myself up on all fours, shaking my head to clear what I euphemistically call thoughts. Coughing up seawater and struggling to breathe, I fought my way back to the wheel. Through salt-encrusted eyes redder than the devil’s business card, I could barely make out the compass and our present course. The heading only a few degrees off our safest route.

Taking a firm grip I turned the wheel three spokes to port. The resistance felt strangely light. The compass remained obstinately fixed on the same heading. When another two spokes to port brought no result, I began to worry.

Just then, my partner, Meggi, who had been safely ensconced in our aft cabin bunk, slid open the hatch and stuck her head out. Screaming to be heard over the raging wind, she informed me an ungodly great rending crack come from where the steering ram is located behind our bunk.

Leaving the helm to Meggi, I made my way to our cabin. Salt water and blood dripped onto the cabin sole from a deep cut on my forehead as I lifted the steering box cover. What I discovered came straight from a nightmare. Our hydraulic steering ram shaft, machined from one-inch-diameter high-tensile steel, had shattered like a cheap plastic toy, leaving the tiller arm free to thrash back and forth in those savage seas.

Vega was out of control. Only the drag generated by those long mooring ropes, tightly attached to the stern bits in great loops, and the thrust of our small storm jib held her before the waves. Without steering, there was nothing to stop Vega broaching sideways and being rolled mercilessly into oblivion. The scream of tortured wood from the aft mooring cleats did nothing to relieve my worries. Should one of those cleats give way . . . well, that was a thought simply not worth having.

It was then the real horror of our situation dawned on me: the rudder was not only swinging from port to starboard, fully at the mercy of the sea, it also rocked from side to side, a horrifying indication at least one of the pintles broke.

If you’re not up to date on traditional ship design, rudder pintles are hinges attaching the rudder to the ship, allowing it to rotate when the wheel turns. Vega has two on her rudder and a stout bearing under the rudderstock. Should both pintles break, there would be nothing to stop our violently gyrating rudder from detaching itself and disappearing into the depths below.

Followed by a splash of seawater, a sopping-wet Meggi came down the aft hatch, to inform me the boat would not steer. Seeing me full on in the light of the aft cabin, the look of near panic on her face changed to one of serious concern.

Feeling helpless, in the middle of a raging storm, soaking wet, unshaved for days, and squinting at the world through tortured red eyes, I resembled a macabre escapee from the haunted house of horrors. Blood trickled from my nose and a nasty forehead cut. Add the terrified look etched on my face, and you’ll understand why Meggi’s mouth dropped open.”

Of Tillers and Davy Jones

They say time flies when you’re having fun. What they fail to mention are those moments when time simply shrugs her shoulders and wanders off looking for a cold margarita: leaving you in timeless limbo to get on with whatever you’re doing as best you can. Mind you, I fully understand her attitude. In those moments, if it meant being somewhere else, I gladly pay the first round, and maybe even a second—with peanuts.

An insane roll threw me across the aft cabin to fetch up against the side with a painful thump. Dancing around on the madly gyrating deck, I yelled for Meggi to get out the emergency tiller, while I fought my way on deck and retrieved two pieces of stout braided line. Extremely strong and highly resistant to abrasion, that rope was perfect for an emergency rudder repair.

As my head emerged from below, the wind nearly blew my hair off. While rigging screamed in torment, raging winds shattered the wave crests into a froth of driven spray before hurling foaming white horses into the troughs. Struggling to breathe, and reflecting on how Dante would love this place, I fought my way to the forward line locker.

Having a bright idea and making it work are often quite different propositions, especially when they involve a wildly gyrating deck and a rudder violently swinging from side to side every few seconds. What, on a calm day in port, might take only minutes to accomplish became an endless eternity of individual seconds. Each accented by its own specific danger, and the constant fear of sudden death looming over it all.

Before the emergency tiller could be slotted in place, I first needed to dismount the shattered steering ram. This involved removing a tight-fitting stainless-steel pin held in place by a reticent split pin. Just getting the split pin out became a major effort, involving pliers, hammers, bashed fingers and copious amounts of creative profanity. Then pulling the locking pin, normally an easy job, turned into a marathon of horrors. Through it all, I was constantly under attack by a wild flailing rudder and its heavy iron steering arm.

Being in a state fast approaching panic didn’t help. The strange thing about life-or-death situations is how they focus your mind quite clearly in two different directions. One instinct is to widdle your knickers and hide under the bed: bum in the air and a pillow covering your head. Mean while the other little voice between your ears screams demands to do something before you find out if there really is a scythe wielding specter on the other side.

With the remains of the steering ram out of the way, another interesting little quandary presented itself. How to firmly reattach the rudder head to the boat so once I installed the emergency steering tiller the rudder would actually pivot and not simply flop from side to side. That is where my two pieces of braded yacht line came into play: if I managed getting them in place without losing a handful of fingers—or worse.

Fortunately, there is a space between the steering arm and the rudder head. If I fed the two pieces of line through there, and boused them tightly to the sides of the boat, together they would hold the rudder head, in place. More or less.

Getting those two lines through such a small space, while retaining all of my appendages, and avoiding a short sharp smack on the head from the flailing rudder arm proved more difficult than it sounds. What on shore, I could do it in a minute or so, took ages at sea in a storm. As my imagination vividly portrayed the boat swinging wildly out of control, each adrenaline powered second filled with anxiety: fueling the fear of impending dissolution. How long it really took? I have no idea.

Once threaded between the rudder head and steering arm, I anchored those lines firmly behind the beam shelf: effectively wedged against two stout frames. That done, and after several anxious moments getting the close-fitting emergency tiller slotted over the steering arm, we could steer again. Why we were still alive, and not well on our way to Davy Jones’s locker, remains an unsolved mystery, for the effort seemed to take hours.

While I cursed reticent lines and rudders in general, and sucked on fingers mashed with disconcerting regularity, Meggi duct-taped our hand-bearing compass to a deck pillar.

With the emergency tiller in place and a compass to steer by, I gave the tiller an almighty shove to starboard. Nothing happened. Employing all my strength, I barely managed to shift the thing by a few degrees.

Little wonder. The original tiller on Vega measured almost five meters and required one, sometimes two, standing men to shift it. The emergency tiller our lives now depended upon spanned slightly more than one-meter-fifty, and could only be operated from a sitting position.

Calling our two young crewmen, I put one on each side of the tiller and gave them a course to steer. It’s amazing what fear does for strength and endurance. Considering the wild gyrations our boat made just staying in one place was a major effort, much less applying force to steer. Yet somehow, those two intrepid lads managed to wrestle us back on course.

Leaving them grunting and groaning over the tiller, I went in search of a few pulleys and some line to rig up relieving tackle: a devious sailorly invention consisting of four blocks rigged on a single line so when half the tackle pulls, the other half pays out. In our case, the four-to-one mechanical advantage I cobbled together allowed one person to steer the boat, more or less.

Lightning illuminated the aft cabin, quickly followed by an almighty explosion of thunder so close that it rattled my teeth. We might have steering again, barely, but the fight for survival was far from over.

Next?

"I still haven’t settled on a title for the current book I’m working on about rescuing an abandoned 100-year-old wooden sail boat from a deserted beach in West Africa. With only $2.38 in my pocket and a whole lot of “I want a boat”, I embarked on a dream. Months of hardship, suffering, and good luck later, that fantasy became a floating reality. Filled with wonderful times and hair-raising experiences beginning by almost crashing into an aircraft carrier on the first test sail and then being dragged across one of Africa's most nefarious reefs on the second day at sea. Young, inexperienced, and full of illusions, tropical storms, a boat full of water, and crossing the Atlantic alone without a functioning rudder lay in my future."